Fort Floyd Cherokee Internment Site

Fort Floyd Historical Marker

This article is adapted from "Cherokee Removal: Forts Along the Georgia Trail of Tears" by Sarah H. Hill.

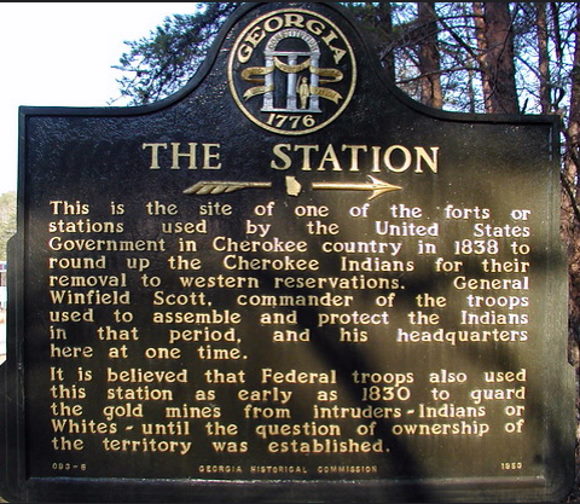

The most helpful sources for Ft. Floyd, Dahlonega, are the National Archives records of the Quartermaster’s Department. Initially, we were not certain that any kind of post was established in Dahlonega, but the commitment of Trail of Tears charter members Dan and Dola Davis encouraged considerable research. The 1954 location of a state historical marker at a site called “The Station” five miles south of Dahlonega complicated the process since no primary documents could be found to connect the Station to the removal of Indians. The 1932 publication of Andrew W. Cain’s History of Lumpkin County convinced many readers that “The Station” was the site of Gen. Scott’s headquarters where “hundreds of Indians were brought.”cxlix Cain’s source was a published (but not referenced) article by Col. W. P. Price, whose father was said to have participated in the removal. Other writers followed Cain and used various names for the post at Dahlonega including Ft. Dahlonega and Ft. Lumpkin, neither of which existed.

Correspondence found in the Georgia Department of Archives and History refers to Camp Dahlonega and Cantonment Dahlonega, indicating the 1838 existence of an unfortified post. In contrast to the information on the historical marker, no evidence has emerged to connect the 1830 occupation of gold mine areas with the site of the removal post. Two trips to the National Archives in Washington uncovered a trove of material relating to Ft. Floyd and its role in the distribution of subsistence supplies to four other posts. We are now certain that the militia constructed a fort in Dahlonega in conjunction with the removal of Indians. It is unlikely that any Cherokee prisoners were ever kept in a camp or garrison in Dahlonega, but since the records from Gen. Eustis in North Carolina have not been located (and the garrison in Dahlonega reported to Ft. Butler), we cannot yet be certain.

Dahlonega.

Dahlonega, from the Cherokee word taloni ge (yellow), was incorporated at the December, 1833 session of the state legislature. Previously called Licklog, the town was made the seat of Lumpkin County, which was created in 1832 and named for Gov. Wilson Lumpkin. Gold had been found in the nearby Chestatee River as early as 1828, which led to a population explosion of itinerants as well as settlers. By the time of its incorporation, Dahlonega already had a log courthouse, soon followed by dozens of houses, stores, taverns, and more than a thousand residents.cl In 1836, the log courthouse was replaced by one of brick and mortar.cli

The importance of Dahlonega in the larger economy is evidenced by construction of the Dahlonega branch of the U.S. Mint, which began in 1835. Located on a ten-acres tract on a knoll south of the town square, the site chosen for the mint already had a working well and several buildings.clii Between 1835 and the commencement of removal in May 1838, workmen struggled with fifty thousand pounds of mint machinery and construction materials. The first coins were minted April 17, 1838, scarcely a month before removal began.cliii The presence of the mint and the abundance of gold were important factors in the decision to establish a post in town. As it turned out, the presence of the mint affected the selection of the site for the post.

Since Dahlonega was incorporated by the state legislature, it was never considered a Cherokee town. Its location in the foothills of the Blue Ridge with proximity to the Chestatee and Etowah Rivers and Cane and Yahoola Creeks made it a desirable location for white settlement. Nearby lay the established Cherokee communities of Frog Town, Chestatee Old Town, Bread Town, Amicalola, Tensawattee Town, and Big Savannah. Many Cherokees along the Chestatee and its tributaries signed up for emigration in 1832, but as late as 1836, at least 17 Cherokee families lived on Tennsawattee Creek, 28 on Amicalola Creek, and more than 13 in Big Savannah on the Etowah River.cliv Along the Etowah just west of Dahlonega, whites who had intermarried with Cherokees farmed sizeable plantations. Daniel Davis, Silas Palmour, and three Davis sons-- William, Martin, and John—owned homes, orchards, mills, slaves, and river land as well as upland.clv All were considered citizens of the Cherokee Nation.

Military Occupation.

Records reveal an unusual amount of confusion regarding the militia occupation of Dahlonega. Apparently the lines of authority were not established since Gilmer, Scott, and various members of the quartermaster’s department were all making military decisions. In December of 1837, Gilmer called for an infantry company to be stationed in Dahlonega but did not specify which one.clvi At the end of January, Gilmer wrote that Capt. Lewis Long’s Habersham Rifles were going to Dahlonega but Long then disappears from the records.clvii In early February, Gilmer again wrote that a recently-received (unnamed) Georgia company would be posted to Dahlonega, but soon afterwards Gen. Scott sent a Tennessee company commanded by Capt. Peake to the site.clviii

Meanwhile, local residents competed with one another to enter the service, and Gilmer received numerous letters of protest from frustrated citizens who considered themselves the most valid members of the Dahlonega volunteers. Finally, in mid-February, two months after Gilmer’s first call, Capt. Peake arrived in Dahlonega with quartermaster A.M. Julian, who selected a position “as near the U.S. Mint as I could.”clix On Feb. 26, however, the Mint supervisor wrote Gilmer that “the company destined for this place” had not arrived and he had heard that they were not coming.clx

The final occupation was not yet set. Georgia militia Cpt. (Lewis) Levy of Habersham County and (1st Lt. James?) McGinnis (of Gwinnet County) were reported ready for muster and posting to Dahlonega on the first of March.clxi Less than two weeks later, Capt. Peake’s quartermaster wrote that he had learned that Levy could not raise his company and would, therefore, not come to Dahlonega.clxii Peake’s company left soon after and in mid-March, Capt. Benjamin Cleveland, Jr. of Franklin County was assigned to take command of the post.clxiii Although he arrived unsure of his final command, Cleveland remained until the completion of removal.

Cleveland was a seasoned soldier, having served in the War of 1812 under Andrew Jackson. When he mustered in at Ft. Butler, North Carolina for the removal of Cherokees, he was 46 years old and commanded a company of

93 men.clxiv Important details regarding Cleveland’s command remain unknown because he was assigned to the Eastern Military District under the command of Gen. Eustis, whose records were not found in the National Archives. Additional research will be necessary to find more about Cleveland in this unusually important post.

In addition to Julian, Lt. A. Montgomery acted as Dahlonega quartermaster for some part of March. Pvt. James Ratcliff served as Cleveland’s quartermaster, but by April 8, V. M. Campbell arrived from Ft. Foster to supervise the quartermaster departments at Dahlonega, Coosawattee (Ft. Gilmer), Ellijay (Ft. Hetzel), and Sanders (Ft. Newnan). Campbell later received responsibility for the camp at Chastain’s as well. Ratcliff remained, however, even though he pointed out to Lt. Hetzel of the quartermaster department at Ft. Cass that he had no experience.clxv

More...

>